Transferable tax credits are a transformative mechanism to accelerate investments into US energy and manufacturing. Transferable tax credits provide notable advantages for developers and manufacturers, streamlining tax credit monetization for sellers while reducing tax liability for buyers.

In this guide, we’ll review the essential information that transferable tax credit buyers, sellers, and intermediaries need to know to leverage this opportunity fully, including:

Sign up for The Crux of It newsletter to keep up with the latest market insights

The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in 2022, permits certain federal clean energy and manufacturing tax credits to be sold for cash, creating a more efficient way to deploy and recycle capital. Buyers earn a discount on the credits, reducing their tax liability and making participation in clean energy finance more appealing. These private transactions take the place of grants or government refunds, which require the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to directly arbitrate the provenance of a credit.

The ability to freely sell tax credits in a robust private market has several distinct advantages:

The impacts of transferability are already on display — transferable tax credits have catalyzed more than $500 billion in private capital since 2022.

The 11 federal tax incentives for clean energy are:

Before tax credit transferability, various forms of tax equity were the only external mechanism to monetize project tax attributes. In a tax equity relationship, “tax investors” invest directly into partnerships with developers and receive a special allocation of cash, tax credits, and depreciation in exchange.

Being a partner in a tax equity transaction is structurally complex and generally requires domain knowledge and monitoring and oversight capabilities. As a result, tax equity has principally been the domain of banks and insurance companies — the 10 largest tax investors comprise the vast majority of the market.

Transferability is still a private market mechanism. It relies on the private sector to conduct appropriate due diligence, preventing fraud and ensuring that buyers and sellers in tax credit transfer deals retain “skin in the game.” But unlike tax equity, transferability opens the market to any and all investors interested in clean energy finance, providing new flexibility to find and capitalize on opportunities. This means that transferability is driving innovation not only in the investment world but also in energy infrastructure.

That investment comes at an opportune time — energy demand is rising for the first time in decades, driven by artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing, and domestic manufacturing. Transferability provides powerful incentives to invest in and build the energy infrastructure that will be required to deliver reliable, affordable electricity.

Historically, zero-emissions energy project developers were required to enter joint ventures and leasing arrangements with other private companies with sufficient tax liability to capture the full value of the major clean energy tax credits, such as the investment tax credit (ITC) and production tax credit (PTC). These arrangements are known as "tax equity" and are relatively complex financing structures.

This stipulation has created a bottleneck in deploying clean energy over the last several decades. Generally, only large financial institutions with project finance underwriting capabilities and a small cohort of non-financial companies have been repeat "tax equity" investors.

Transferability opens access to more developers and manufacturers — smaller developers historically have not been able to access tax equity. Now, though, all developers can sell credits in the transfer market, making capital more accessible.

Transferability also creates opportunities for a wider range of technologies. While tax equity has historically been limited to established clean energy technologies such as wind and solar, transferable tax credits have a broader scope, including nuclear, hydrogen, geothermal, biogas, and advanced manufacturing.

This flexibility not only drives economic growth in terms of domestic manufacturing, but also incentivizes innovation in the development and commercialization of next-generation clean energy technology.

The tax credit transferability feature for various clean energy tax credits included in federal legislation allows a larger universe of corporate taxpayers to take advantage of the credits because they do not require complicated tax equity structures. Tax credit transferability is a simpler structure and should entice a much bigger pool of corporate taxpayers to participate in clean energy project financing.

With more buyers, a larger pool of developers and manufacturers should benefit from the ability to monetize their tax credits and the simpler process for doing so. Tax credit monetization plays a significant role in capitalizing clean energy projects, so more capital access should be a catalyst for many developers and manufacturers, especially those that may not have established relationships with tax equity providers.

Syndicators, tax advisors, and other intermediaries also play a critical role in connecting buyers and sellers, structuring transactions, and conducting due diligence on tax credit transferability investments.. While transferability streamlined the process for project developers to monetize their tax credits, this transaction is still complex. Buyers and sellers should continue to engage their advisers throughout the process.

At Crux, we're creating the capital markets platform that will enable all industry participants to scale their businesses and maximize opportunities in the transferable tax credit market:

Our network and tools will help all parties streamline the transaction process, access a large and liquid market, and reduce risk through our market-standardized documentation and advisory partners — facilitating more transactions to supercharge the clean economy.

We also know that these transactions are and will remain complex and bespoke for some time. Crux enables better coordination between credit buyers and sellers, as well as their advisors, lawyers, and other partners.

According to the IRS, eligible entities that wish to pursue a transferable tax credit transaction may take the following steps (noting that not all steps need to occur in the order listed below):

Transaction process for transferable tax credits

Sellers and buyers complete a transfer election statement, including the registration number, which is attached to the sellers and buyers’ tax returns. Importantly, according to Treasury guidance, “not all steps need to occur in the order displayed,” and “a transferee taxpayer may take into account a credit that it has purchased, or intends to purchase, when calculating its estimated tax payments.” This process principally affects filing and does not prevent deals from being signed and funded.

As developers and buyers evaluate the tradeoffs between tax equity and transferability, many are focused on two key value drivers:

Tax equity inherently solves for both of these drivers. For transferable tax credits, project owners and sponsors consider a number of options.

For many developers, the ease and speed with which they can execute transferable transactions will outweigh the potential loss of step-up and associated tax attributes, as well as the inability to immediately monetize depreciation. Many developers can monetize some level of tax attributes internally or via their sponsors or affiliated entities.

In other hybrid structures, developers are sizing tax equity to a certain return or allocation — allowing them to monetize the depreciation and achieve an appropriate step-up — and planning to use transferability for the balance.

Some are using other structures to attempt to achieve a step-up, including selling the project into a partnership with a third-party. There are a range of opinions as to what types of partnership structures are sufficient to achieve this valuation step-up, depending on the unique needs of various developers and manufacturers.

Advisors play an important role in providing diligence, insurance, and indemnification for buyers of transferable tax credits. While these roles are similar to those performed in tax equity deals, the tax credit market is expected to streamline transactions, leading to:

A credit buyer’s critical review will focus on:

Stakeholders will look at appraisals, cost segregation reports, and legal/tax opinions.

Buyers will also want to ensure that the typical series of project documents are in place (e.g., engineering, procurement, and construction agreement, interconnection agreement) and evaluate the credit support and creditworthiness of the developer.

Indemnities may be an area where tax credit buyers focus more than tax equity investors, as they do not have the downside protection of being part owners in the project.

Insurance plays a large role in tax credit transactions, especially in transactions involving smaller or non-investment-grade developers. In addition to property & casualty insurance, tax insurance policies are actively being bound on transferable credit transactions, with a focus on insuring against recapture and disallowances of eligible basis.

Crux has observed insurance coverage levels below 100% in situations where insurance is a credit enhancement tool for a seller. However, insurance coverage ranging from 90–140% is substantially the most common coverage percentage. A small portion of deals include coverage in excess of 140%, up to 165%. The seller typically covers the cost of insurance coverage, which ranges between 1.5% and 3.5% of the total transaction cost, depending on coverage and sizing.

Any eligible taxpayer (under the IRS definition) can take advantage of tax credit transferability, meaning that tax-exempt organizations are generally ineligible. Corporations and even individuals can buy tax credits.

While the buyer can be an individual, they will be subject to active and passive activity restrictions — meaning that the face value of tax credit transferability can only be used to offset tax liabilities from passive, non-investment income.

Some high-net-worth individuals and family offices that have previously participated in the tax equity market may find transferable tax credit deals appealing if they can time the payout closer to their tax filing date. However, we do not expect the tax credit transferability market to open widely to individuals.

Credits are typically sold at a discount to their face value, indicated as cents on the dollar (e.g., a $0.93 TTC price indicates a 7% discount to the face value of the tax credit).

Average price by deal size tranche, PTC and ITC, 2024

Internal rates of return on tax credit transactions are particularly high, and corporations are doing their best to time credit purchases as close as possible to their quarterly estimated payments. Most taxpayers set aside cash to make tax payments, including quarterly estimated payments.

Those funds would not normally generate a return; companies cannot choose between paying taxes and building factories. With tax credit transferability, reserved cash suddenly has the capacity to generate a real cash return, making transferable tax credits a uniquely attractive investment.

Transaction costs can include fees for advisors and syndicators and for conducting due diligence. We find that the seller of the credit typically covers these fees up to a negotiated cap.

With transferability, the risk of the IRS not respecting the tax equity partnership as valid is eliminated because no partnership exists. However, there may still be a need to demonstrate the true third-party nature of the transaction. Project cash flow risk is much less of a concern so long as the project remains operational and solvent, given that the tax credit buyers do not participate in the project cash flows.

Still, there are some key risks that buyers and sellers will have to navigate, particularly in the case of ITCs:

In the context of transferable tax credits, recapture is the risk that tax credits may be reclaimed if the project fails to meet certain requirements. Generally, developers will have to continue indemnifying buyers for this risk as they have historically done, and insurance will play a key role. Even with insurance, project viability will remain important to buyers. Credit buyers won’t participate in project cash flows but will still need to be confident the project will remain in service through the five-year recapture period.

As with tax equity, the developer will be responsible for maintaining and operating the system throughout the recapture period and supporting whatever indemnities it gives to the buyer. A developer declaring bankruptcy and abandoning a project could trigger recapture. A benefit of transferability is that, after the recapture period, the transaction with the tax credit buyer is fully resolved.

One of the more important risks is ensuring that the stated basis level is eligible for tax credits. Credit sellers are historically accustomed to “stepping-up” the value of a development project through a sale to a tax equity partnership before monetizing the credit to validate the value through third-party investment. While this practice is commonplace, the valuation of such items requires careful monitoring and evaluation. Developers generally share the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) agreement, as well as an appraisal and cost segregation report, as part of diligence.

Many of these risks related to recapture are typically covered by insurance. The seller of the tax credit will commonly cover insurance costs, though buyers can also choose to purchase uninsured credits at a steeper discount.

Federal tax policy entitles the tax credit buyer to carry the transferable tax credit forward for 22 years and back for three years, meaning that the buyer has up to 22 years of future tax filings to utilize the full value of the credit. They can also carry the tax credit back and apply it to previous years, as far as three years in the past.

However, the carryback is not as simple as applying the credit to the previous year’s return:

Companies will have filed tax returns during these periods, so applying tax credits to previous years requires refiling taxes for as many as three previous tax years, and thus may be a prohibitively complex process.

Carryback process for transferable tax credits

In the rapidly developing transferable tax credit market, one of the biggest challenges is the timing gap (like in the tax equity market). Developers and manufacturers want to move forward with as much certainty and commitment as possible, while buyers want to outlay cash as close to quarterly estimated payments as possible.

With that in mind, recent final guidance from the IRS has confirmed that transferable tax credits can be applied to tax liabilities in the same year they are generated. This means buyers should complete the purchase before the end of the tax year so they can claim the credits.

It’s also important to remember that the seller and buyer must complete the IRS pre-filing process, which can take several weeks. Timing deals and negotiations correctly is critical.

Learn how Crux can help you navigate the transferable tax credit market

In general, buyers seek to align purchases of transferable tax credits with their quarterly estimated tax payments. Buyers also assume certain risks when purchasing tax credits and, as such, are likely to pay more for credits that are perceived as being lower risk.

While the market for tax credit transferability is still fairly new, it’s maturing quickly. We see transferable tax credit pricing organizing into tranches with pricing estimates reflecting relative risks (as discussed above).

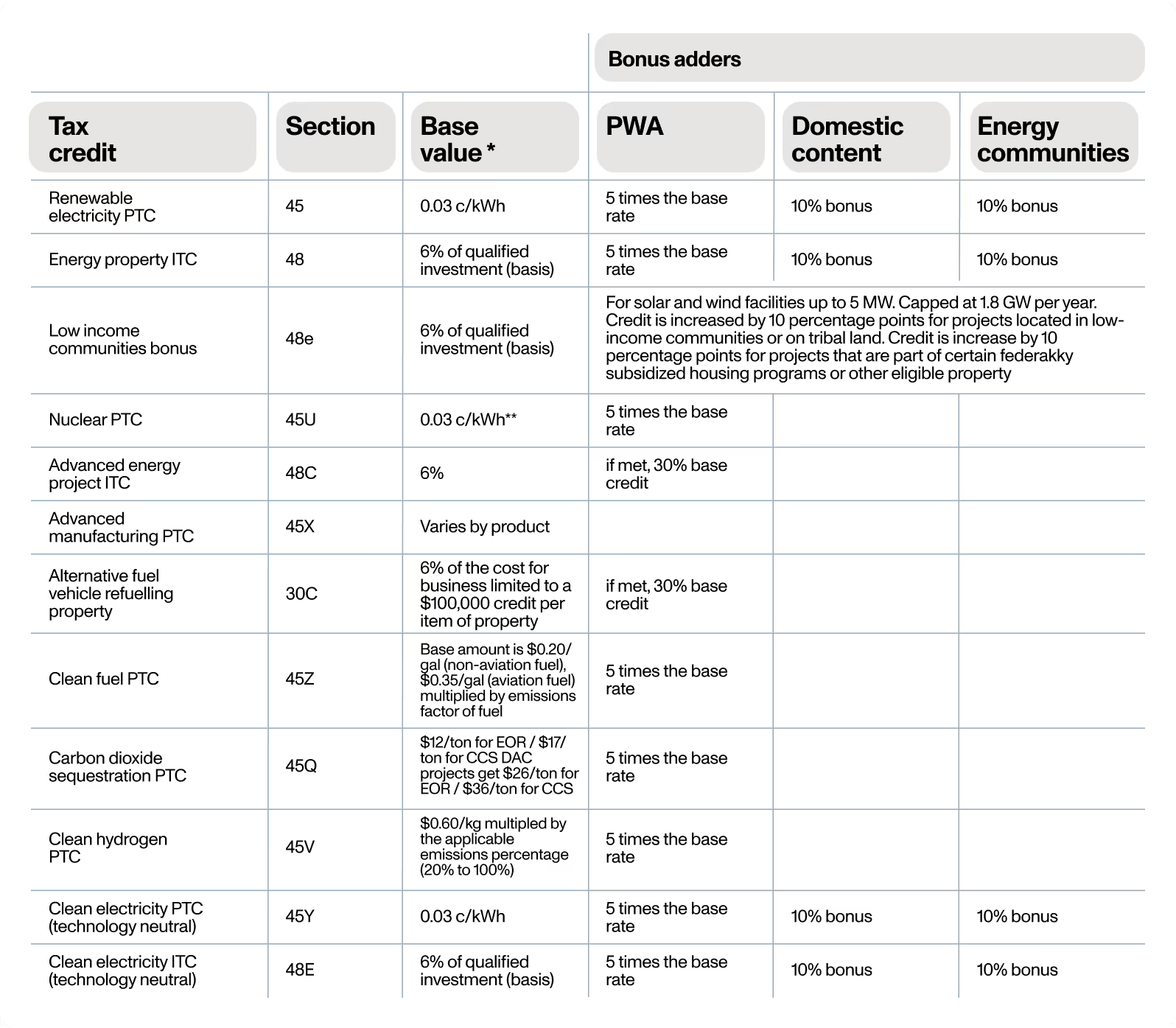

Federal tax policy provides valuable bonus tax credits (also known as “adders”) for projects that meet certain criteria.

Tax credits with applicable bonus adders

The prevailing wage and apprenticeship (PWA) bonus tax credit is available to projects to demonstrate that they met certain pay thresholds and apprenticeship requirements throughout construction and in the five years after the project enters service. Projects that meet this requirement can take a 5x multiple on the base 6% ITC rate — boosting credits to 30% of the project’s cost.

Projects that started construction by January 29, 2023 were grandfathered into the 30% ITC rate and do not have to demonstrate that they meet the PWA standards. Projects reflecting PWA adders are generally the standard baseline.

Another valuable tax credit bonus is available to projects that meet domestic content adder requirements. In the proposed guidance, the IRS indicated that companies must demonstrate that projects meet domestic content standards for steel or iron constituent parts and manufactured goods.

If a project meets these standards, it can claim an additional 10-percentage point bonus tax credit, boosting its ITC value to 40% of its base cost from 30% (for projects that meet PWA requirements).

Projects developed in communities or census tracts designated as energy communities can claim an additional 10-percentage point increase in credit value. The IRA defines energy communities as:

Projects developed in low-income communities or communities designated as historic energy communities may access additional bonuses. The low-income communities bonus tax credit program is available to solar and wind projects under 5MWac that are installed in low-income communities or on tribal land.

Projects meeting these benchmarks can access a 10% bonus above their baseline ITC or PTC rate. Alternatively, a 20-percentage point credit increase is available to eligible solar and wind facilities that are part of a qualified low-income residential building or a qualified low-income economic benefit project.

Sellers typically cover transaction fees up to a negotiated cap. In addition to these fixed costs, the gross purchase price for transferable tax credits would include costs associated with insurance and transaction fees. Insurance costs can be 1.75–3.50% of the face value of the credit (depending on deal size and risk), and deal fees range from 0.5–3.0%.

For instance, if a project sponsor sells a credit for $0.90 gross (a 10% discount to the face value of the credit), obtains insurance for 1.75% of the face value of the credit, and pays a fee to an intermediary or broker for 1.25% the credit value, they will realize net proceeds of $0.87. If the buyer of the credit incurs $50,000 in additional advisory fees related to conducting due diligence of the transaction, and the seller has agreed to cover these fees up to that amount, then these costs, too, would be subtracted from the transferable tax credit sale to estimate the seller’s proceeds.

Transferable tax credit transaction timelines vary depending on numerous factors but tend to be faster than tax equity transactions. The fastest deal Crux has observed closed in 17 days, but most take a few months, whereas tax equity deals typically take the better part of a year to close.

For investment tax credits, the tax credit is generated when the facility is complete and placed in service. Importantly, projects that intend to claim the ITC but have regular, multi-year construction timelines may claim partial credits for qualified production expenditures (QPEs). These QPE credits are not eligible to be sold or transferred; only the ITC generated in the year the project is placed in service can be transferred.

Production tax credits are generated after a project enters service and begins producing energy. PTCs are generated for each unit of production (e.g., a megawatt-hour of electricity or a kilogram of hydrogen) for a long period of time — 10 years under the new federal tax policy.

Developers and manufacturers can sell forward a stream of future PTCs (or a “strip”), either as a production tax credit deal or as a tax equity transaction. Typically, a developer or manufacturer will sell a conservative estimate of their future PTCs in a forward transaction to minimize the risk that the facility will not generate enough energy in a year to meet the required supply of PTCs. Excess PTCs generated in each year can also be sold as “spot” PTCs, which must be sold in the tax year in which they are generated (or before the extended tax filing date for that year).

Buyers of tax credits often choose to execute transactions as close as possible to the end of their tax year (when they have the greatest certainty around their tax liabilities).

For developers and manufacturers, it may be necessary to procure bridge financing to access cash before the tax credits are generated/sellable.

Crux has observed that lenders are entering the market to provide this capital, and that the market for transferable tax credits appears reliable enough to lend around.

Whether you’re a developer or manufacturer, buyer, or intermediary, Crux can help you make the most of the transferable tax credit market. With our extensive network, tools, and access to the largest market, we’ll help you streamline your transactions and reduce risk.